Updates & Blog

10 Things You May Not Know About Wildfire Deployments

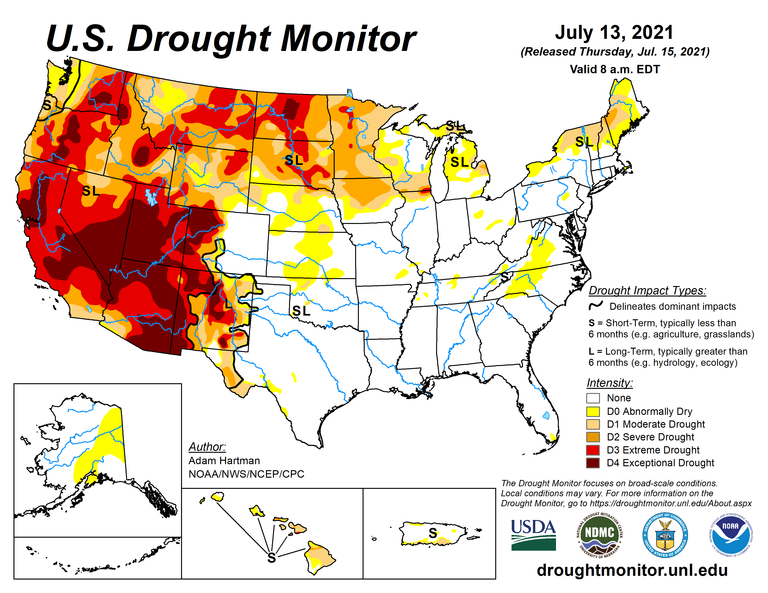

Recently, the United States shifted into Wildfire Preparedness Level 5, the highest possible level of wildfire activity on the scale. This preparedness level indicates the numbers of firefighting resources, specifically incident management teams, overhead, crews, aircraft and equipment, deployed to battle wildfires nationally. Many of these resources come from the southern states, where wildfire risk and activity are currently at a lower level. As of this writing, the Southern Area has dispatched employees from states to Montana as part of a Type 1 Interagency Incident Management Team, numerous 20-person hand crews to California and Montana from Florida, Mississippi, Tennessee and Texas, an engine task force to Washington from North Carolina and Kentucky, and a host of other team and individual overhead deployments (for up-to-date overhead dispatch information, visit the Southern Area Coordination Center website).

Here are 10 things you may not know about wildfire deployments:

1. Deployments are made possible through a formalized partnership

State forestry agencies deploy many personnel, crews, equipment and aircraft to wildfires, emergencies or major disasters – including deployment to the current wildfires in the western U.S. They do so through a formalized partnership with federal land management agencies called the “Master Cooperative Wildland Fire Management and Stafford Act Agreement.” This agreement allows for efficient sharing and exchange of resources and funds to support wildfire management and response across the country (costs associated with deployments are covered by the host agency/incident).

2. It’s a balancing act for home states

State Foresters and their Fire Management Chiefs monitor their own wildfire/emergency risk to ensure their home states continue to have adequate staffing and resources. State forestry agencies will allow out-of-state deployments only after determining that doing so will not add undue risk to the state.

3. Staff are ready to deploy at a moment’s notice

Qualified individuals place themselves, through their home forestry agency, on the Interagency Resource Ordering Capability (IROC) availability list. During their listed availability period, they must be ready to immediately dispatch for at least 16 days (including travel).

Each available individual will have their firefighting line gear (or other equipment necessary for their specific assignment) and personal gear bag packed and ready to go. Typically, a person is limited to 65 pounds of line gear and personal items when travelling to an out-of-state wildfire assignment. Essential items may include personal protective equipment, handheld radio, tent, sleeping bag, clothing, and toiletries.

4. Deployed staff may “rough it” in remote locations

Wildland firefighters and other staff often stay in primitive camping arrangements during the duration of their assignment. While not every incident requires staff to camp, many wildfire incidents are in remote areas with rough terrain where hotel accommodations do not exist. These areas can also have unreliable or non-existent cell service. In these cases, a call to a loved one at home is sometimes a precious rarity. For large-scale or complex incidents, camp life can sometimes be more comfortable with hot-plate food service, temporary cell towers (used also for supporting operations) and portable shower and restroom facilities.

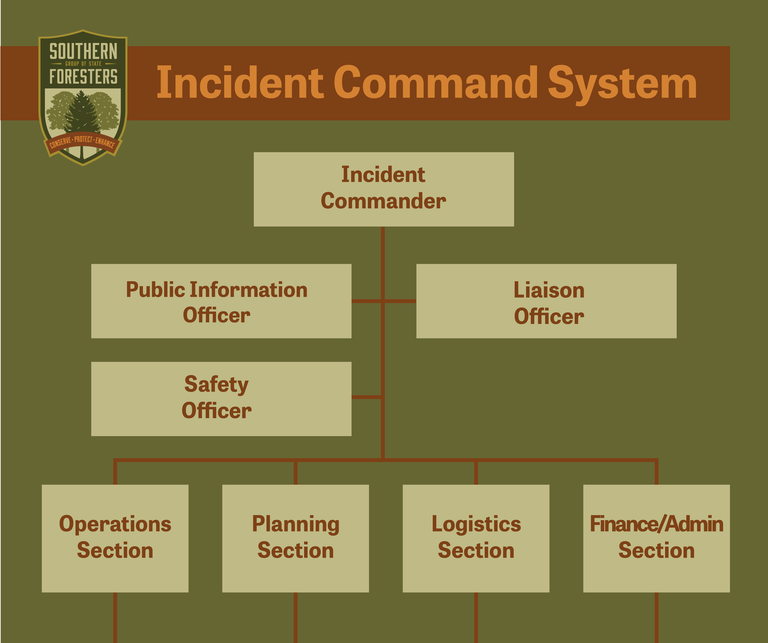

5. All incidents are managed using the Incident Command System

All staff working on wildfire assignments are trained to work within a scalable incident command structure called the Incident Command System (ICS). According to the National Wildfire Coordinating Group (NWCG), ICS is a “standardized on-scene emergency management concept specifically designed to allow its user(s) to adopt an integrated organizational structure equal to the complexity and demands of single or multiple incidents, without being hindered by jurisdictional boundaries.” ICS is a well-organized team approach that helps responders quickly establish (and transfer) chain-of-command and manage personnel, resources and communications, no matter the size or scale of the incident.

6. Wildland firefighter is one of many roles on a wildfire assignment

There are many roles within a wildfire incident. The command & general staff consists of an incident commander, public information officer, safety officer and liaison officer, as well as section chiefs for operations, planning, logistics and finance/administration. The operations section consists of wildland firefighters of various types, air operations and supervisory roles. Planning section staff provide services such as producing the Incident Action Plan, collecting and analyzing situational data, providing mapping/spatial information, maintaining incident documents and files, human resources, and check-in and demobilization of staff. The logistics section has roles that handle provisions for facilities, services and material in support of the incident, like radio communications, medical, food, supply procurement, and base/spike camp management. Finally, finance/administration personnel are responsible for all financial, administrative and cost analysis for the incident.

7. States may work together to build full teams

Southern state forestry agencies often collaboratively combine personnel from multiple states to fully staff incident management teams (IMTs), crews, strike teams and task forces. Recently, the North Carolina Forest Service and Kentucky Division of Forestry pooled personnel and resources together to form a five-engine strike team to respond to wildfires in Washington.

Additionally, southern state forestry agencies together maintain seven all-hazard Type 1 and 2 IMTs. These teams are fully staffed and self-contained, and are experienced in wildland fire operations, planning, information, logistics, finance and safety. These teams are made up of staff from various southern states and cooperating agencies – some teams consisting of nearly 60 members each.

8. Staff must be trained to their specific assigned role.

All staff that are deployed to an incident must be trained, experienced and certified for their assigned role. State forestry agencies in the South follow the National Wildland and Prescribed Fire Qualification System Guide for minimum qualifications for each position when dispatching personnel on an interagency assignment. Each deployed individual will have already obtained an Incident Qualification Card or “red card,” which is an agency-issued credential certifying that the holder’s level of training, experience and physical fitness meets the need of the requesting agency.

9. Health and wellness are important on wildfire assignments

Staff working on wildfire assignments can experience many long, demanding workdays, so it is important to help manage fatigue and keep staff members safe and healthy. Under NWCG guidelines, all incident staff should typically have a minimum of one hour of sleep and/or rest per two hours of work or travel. Nutrition is also a critical part of ensuring a healthy crew. NWCG recommends that “wildland firefighters on the fireline need [to consume] 4,000 to 6,000 calories a day to avoid an energy deficit.”

10. Staff bring home important skills and experience

When a state dispatches personnel to wildfire assignments abroad, they are not just providing much needed assistance. Sending staff on assignments out-of-state helps personnel keep their skills sharp for use back home. These assignments allow individuals, in all types of incident roles, to hone their skills and gain valuable experience – so that when a large-scale wildfire, natural disaster or emergency incident occurs closer to home, the southern states have agile and practiced teams ready to respond swiftly and efficiently.